The demonization of Israeli “settlers” – those Israelis who live beyond the “Green Line” – is a narrative that is simply reflexive in much of the mainstream media. The Guardian represents an especially egregious case of employing such caricatures to describe Israelis who live outside of the 1949 borders. My tour of the settlement of Eli was an attempt to understand the settler movement and, more importantly, to understand what motivates Israelis to move to communities in Judea and Samaria. Here is my snapshot of the community.

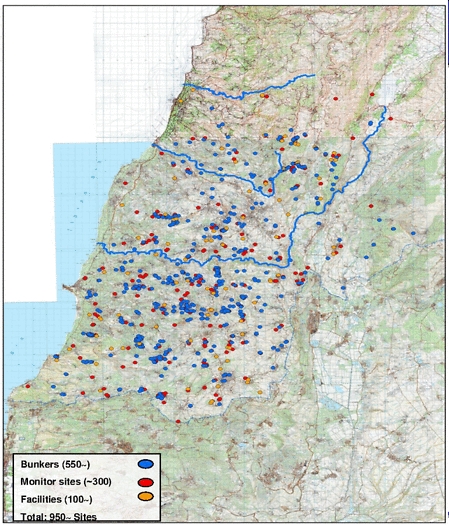

I recently toured the settlement of Eli, a few miles from Ariel, a community stretching over a vast area situated on a mountainous topography, including a cluster of neighborhoods with a total of 3,000 residents. The center of life in Eli is the pre-military academy that attracts religious students from all over the country. Maj. Ro’i Klein, an Eli resident and hero of the Second Lebanon War, was killed when he leapt on a grenade to save his fellow soldiers.

Quality of life is not a vague concept at Eli. There are cultivated gardens, breath-taking mountain views, the shades of its olive trees, and a well-kept regional sports center, which includes multi-purpose playing fields, a tennis court, a work-out facility & swimming pool. Eli provides health services, a small shopping center, and post office. Synagogues and ritual baths are scattered around the neighborhoods.

Eli is also only 30 minutes from Jerusalem. And, the relatively short distance from Israel’s large centers of employment, particularly the Industrial Parks in Barkan and Ariel, allow direct access to and from work. The town is at an elevation of about 700-800 m. above sea level, with a climate similar to that of Jerusalem.

Kobi Eliraz, who is the head of Eli’s local council, spoke to our group with an immense sense of pride about his community. Eliraz is disappointed by most Israelis’ refusal to cross “the eastern threshold of Ariel,” after which the real “settlements” begin. He wanted to also make it clear that he recognizes the authority of the state, and if it wants to evacuate him from Eli, he says, he’ll fight the decision – but peacefully go along with it. Indeed, that sentiment was echoed by others we spoke to.

One of the more interesting things I discovered was that the population of Eli includes a significant number of secular Israelis – inconsistent with the caricature of the settlers as uniformly religious. While I obviously wasn’t able to speak with a large number of residents here, my sense from speaking to the community leaders is that Israelis are drawn to such settlements for a number of reasons. The beauty of the area and relative affordability of home ownership is a factor for some; the allure of living in close-knit, family friendly community is also a draw, as well as the feeling, which I heard echoed by Eli residents – as well as the residents of a tiny outpost near the Jordan Valley that I visited later in the day – that a pioneer spirit was partly at play.

I couldn’t help but think of the American families moving to remote unsettled areas of the Western frontier, in the 19th century, as the borders of their nation gradually expanded – drawn by cheap land, and the promise of a fresh start. No doubt such pioneers thought they were entitled to do so either by political right or by providence. Likewise, Israelis who have opted for these remote hillside communities are also driven by perhaps a sense that, as the original Jewish homeland in Eretz Israel included areas in what we call today the West Bank (Judea and Samaria), they too have an inherent right to settle the areas. But, as the West Bank was captured by Israel in a defensive war (The Six Day War), and not, as in the American example, in the context of expansionist conquest, they no doubt also feel – I think justly so – that they have a strong moral and political claim to the land.

I’m very sympathetic to the settlement community, and am saddened by the degree to which they are often demonized (even by Israelis and Jewish supporters in the diaspora). And, I further feel that Israel’s reluctance to cede more land to the Palestinians, after their experience in Gaza, is completely justified. However, I also feel that, for the sake of a TRUE and LASTING peace, evacuating such settlements may eventually be the the only responsible option.

The devil, of course, is in the details. I’ve argued before, and still believe (based on polling data), that Palestinians are not yet ready to live with a Jewish state within any borders – so, ceding land would not, in the current political context, do anything to advance peace. However, if that day ever comes when Palestinians are truly ready to live in peace with Israel, I think I represent the feelings of many Israelis who think that enormous sacrifices may indeed be worth it if the outcome is a true and lasting peace.

It still wouldn’t be a fair or just outcome for the Israelis who have built homes and communities, and raised families here. But, as politics is rarely about perfect justice – merely about making decisions based on what will cause the least harm – if the decision is between holding onto such settlements at any cost, versus ceding land in return for a genuine peace, I think the choice is a clear one. When it comes to the “settlements”, the axiom that “the perfect is the enemy of the good” has never been more relevant.