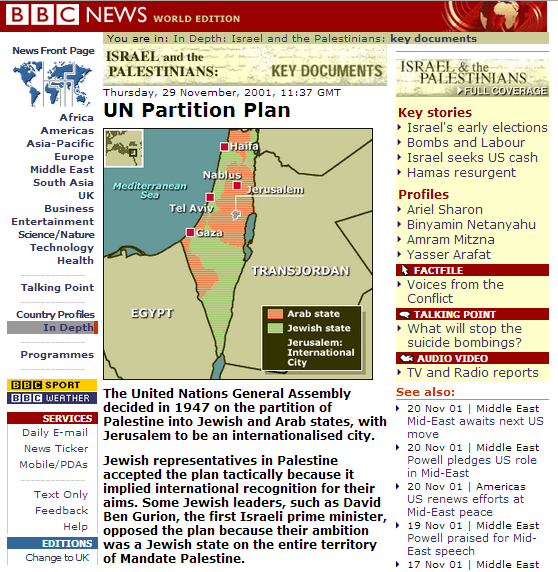

Last Friday (November 29th) marked the anniversary of the 1947 UN GA adoption of the Partition Plan – resolution 181 – which was of course rejected outright by the Arab League and hence became null and void.

Anyone searching for information on that subject on the BBC News website will find a variety of items including maps and articles. One of those articles, dating from 2001, includes a rather curious assertion:

“Jewish representatives in Palestine accepted the plan tactically because it implied international recognition for their aims. Some Jewish leaders, such as David Ben Gurion, the first Israeli prime minister, opposed the plan because their ambition was a Jewish state on the entire territory of Mandate Palestine.” [emphasis added]

No source is provided to back up the BBC’s claim that Ben Gurion “opposed the plan” or how that ‘opposition’ is supposed to have manifested itself. Of course Ben Gurion’s personal opinions on the subject are actually neither here nor there; what is important is the official position taken by the body he represented – the Jewish Agency – and as is well known, that body accepted the Partition Plan.

In the testimony he gave in July 1947 to the UNSCOP Commission (with which Arab representatives refused to cooperate) which preceded the UN vote, Ben Gurion was specifically asked about his views on the subject.

“CHAIRMAN: Do you give preference to a federal State or a partition scheme?

Mr. BEN GURION: We want to have a State of our own, and that State can be federate if the other State or States is or are willing to do so in the mutual interest, on condition that our State is in its own right a Member of the United Nations.” […]

“Mr. LISICKY: (Czechoslovakia): I presume that Mr. BEN GURION has listened to the statement of Dr. Weizmann, which was acknowledged with enthusiastic applause by the public. This statement favours a partition of Palestine into two states. I should like to hear the opinion of Mr. BEN GURION on this scheme-not his personal opinion because it is more or less known, but the opinion of the Jewish Agency. I am not asking for an immediate answer. I should prefer very much a considered opinion of the Jewish Agency after deliberation. If I may ask, I should like to see included in this considered opinion the point of view of the Jewish Agency on the possible federate scheme of these two States-a Jewish State and an Arab State-in Palestine after the partition. I do not mean any rigid federation, but rather a sort of loose confederation, a sort in which the independent character of the Jewish State should be completely set forth. I put the question, but I am not asking for an immediate answer.

Mr. BEN GURION: I will make two remarks on that. One is that Dr. Weizmann is thought so well of by the Jewish people and occupies such a place in our history and among us that he is entitled to speak for himself without any public mandate. You heard his views. I also had the pleasure of listening to them. As you do not insist on my giving you the answer now about the scheme of partition. I will not do it, but I will tell you what we told the Government last year and this year while we believe and request that our right, at least to the Western part of Palestine should be granted in full and Western Palestine be made a Jewish State, we believe it is possible. We have a right to it, but we are willing to consider an offer of a Jewish State in an area which means less than the whole of Palestine. We will consider it.” [emphasis added]

Those are not the words of a man “opposed” to partition, but of someone who both hopes for the realisation of what his nation had already been promised by the allied powers at San Remo, and yet has a pragmatic understanding of the realities facing the Jews living under the crumbling British mandate.

Nearly two months before the UN vote and a month after the UNSCOP report had been published – on October 2nd 1947 – Ben Gurion addressed the Elected Assembly of Palestine Jews with a speech which indicates that he saw partition as a foregone conclusion.

In his book titled “Ben Gurion – A Political Biography” (1964), the former Labour MP for Coventry Maurice Edelman wrote (p 143/4):

“The British Government had carried out its intention of referring the Palestine question to the United Nations. A new commission had been set up known as UNSCOP – the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine – and once again Ben Gurion gave evidence.

Once again a committee reported; but this time a new proposal published on September 1st, 1947, called for partition.

Partition! The Peel Commission had been in favour of partition, but this was a new context. This, at last, seemed the breakthrough to which Ben Gurion had dedicated himself. This was the international endorsement which might be the alternative to the Mandate. This was the miraculous prospect of a Jewish State. Not the nadir of fortune that Weizmann had spoken of, but perhaps – perhaps its zenith. For this, Ben Gurion had fought and toiled, swept Weizmann from power, argued inflexibly with Commission after Commission. This could be the realisation of what his enemies called his madness – the State!”

And what did Ben Gurion himself have to say about his reaction to the UN decision on partition?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IHoc-Sl7jAA]

“When I returned to Jerusalem I saw the city happy and rejoicing, dancing in the streets and a big crowd gathering in the yard of the Jewish Agency building. I’ll admit the truth – that joy was not my lot – not because I did not appreciate the UN’s decision, but because I knew what awaited us: war with all the armies of the Arab nations. […] I can express my impressions in two words: delight and trembling. I was happy, of course, but I was enveloped by anxiety ahead of the invasion of Arab armies…” [translation BBC Watch]

The unsourced, unsupported BBC claim that Ben Gurion “opposed” partition has remained on its website for twelve years and it is clearly high time for that inaccuracy to be corrected. But it is no less relevant to look at the function of that inaccurate claim within the context of the article as a whole.

The only leader on either side named in that article is Ben Gurion and readers are informed that his and others’ ‘opposition’ to the Partition Plan stemmed from “their ambition was a Jewish state on the entire territory of Mandate Palestine”.

The parties which actually did reject the Partition Plan are presented in much softer terms:

“The Palestinians and Arabs felt that it was a deep injustice to ignore the rights of the majority of the population of Palestine.”

No mention is made of Arab ambitions to gain control of “the entire territory of Mandate Palestine” or of the Arab League’s refusal to come to terms with the concept of the existence of a Jewish state. No mention is made of the well-documented threats of violence made by Arab leaders against Jews living in Arab countries should partition go ahead.

The impartiality of this article is severely compromised by its employment of an inaccurate assertion in order to portray the Jewish side which actually did accept partition as intransigent, whilst downplaying the motivations of the Arab side which rejected the UN recommendation.