The BBC’s main backgrounder on the topic of the civil war in Syria – “Syria: The story of the conflict“– includes a brief portrayal of the issue of chemical weapons that makes no mention of the attack in Khan Sheikhoun in April of this year.

Another backgrounder – “Why is there a war in Syria?“, 7 April 2017 – makes just one brief reference to the topic of chemical weapons:

“The US has conducted air strikes on IS in Syria since September 2014, and, in the first intentional attack on Syria itself, hit an air base which it said was behind a deadly chemical attack, in April 2017.”

With the deal that mandated the destruction of the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons arsenal being enshrined in a UN Security Council resolution that was described at the time by the former US Secretary of State John Kerry as “precedent-setting” and by the then UK Secretary of State William Hague as “ground breaking”, the BBC’s funding public would obviously expect to be kept up to date on its implementation and efficacy – not least because British tax-payers contributed to funding the operation.

Last week Reuters published a special report titled “How Syria continued to gas its people as the world looked on“.

“A promise by Syria in 2013 to surrender its chemical weapons averted U.S. air strikes. Many diplomats and weapons inspectors now believe that promise was a ruse.

They suspect that President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, while appearing to cooperate with international inspectors, secretly maintained or developed a new chemical weapons capability. They say Syria hampered inspectors, gave them incomplete or misleading information, and turned to using chlorine bombs when its supplies of other chemicals dwindled.

There have been dozens of chlorine attacks and at least one major sarin attack since 2013, causing more than 200 deaths and hundreds of injuries. International inspectors say there have been more than 100 reported incidents of chemical weapons being used in the past two years alone.

“The cooperation was reluctant in many aspects and that’s a polite way of describing it,” Angela Kane, who was the United Nation’s high representative for disarmament until June 2015, told Reuters. “Were they happily collaborating? No.”

“What has really been shown is that there is no counter-measure, that basically the international community is just powerless,” she added.

That frustration was echoed by U.N. war crimes investigator Carla del Ponte, who announced on Aug. 6 she was quitting a U.N. Commission of Inquiry on Syria. “I have no power as long as the Security Council does nothing,” she said. “We are powerless, there is no justice for Syria.””

In May of this year the BBC produced a report which also highlighted claims that Syria’s chemical weapons programme is still in operation.

“Syria’s government is continuing to make chemical weapons in violation of a 2013 deal to eliminate them, a Western intelligence agency has told the BBC.

A document says chemical and biological munitions are produced at three main sites near Damascus and Hama. […]

Despite monitoring of the sites by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the document alleges that manufacturing and maintenance continues in closed sections.”

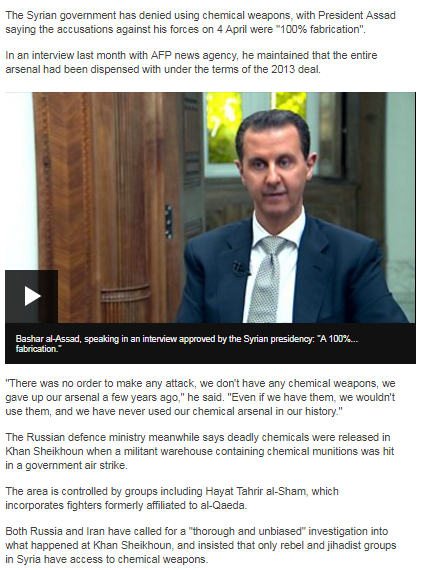

However, that article also gave a platform to propaganda from the Syrian regime – as seen in additional reports.

On August 22nd Reuters published a story concerning chemical weapons shipments from North Korea to Syria.

“Two North Korean shipments to a Syrian government agency responsible for the country’s chemical weapons program were intercepted in the past six months, according to a confidential United Nations report on North Korea sanctions violations.

The report by a panel of independent U.N. experts, which was submitted to the U.N. Security Council earlier this month and seen by Reuters on Monday, gave no details on when or where the interdictions occurred or what the shipments contained. […]

Syria agreed to destroy its chemical weapons in 2013 under a deal brokered by Russia and the United States. However, diplomats and weapons inspectors suspect Syria may have secretly maintained or developed a new chemical weapons capability.”

That story was picked up by numerous media organisations around the world, including Newsweek, the Independent and the Guardian – but not the BBC.

Clearly the BBC could be doing a lot more could be done to provide its audiences with up-to-date information concerning the Assad regime’s failure to comply with the 2013 UN SC resolution 2118.

Related Articles:

Why does the BBC describe the Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack as ‘suspected’?