The April 29th edition of the BBC World Service radio programme ‘Witness History’ – titled “The assassination of the UN’s first Middle East mediator” – was described as follows in the synopsis:

“The UN’s first Middle East mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte, was assassinated in Jerusalem in 1948. A Swedish diplomat and member of the Swedish royal family, Count Bernadotte was killed by Jewish extremists four months after being appointed to try to bring peace to what was already proving to be one of the most intractable conflicts in the world. Louise Hidalgo has been talking to his son, Bertil Berndotte, about the count and his mission.”

The historical background to the programme’s subject matter was introduced by presenter Louise Hidalgo thus:

Hidalgo: “In May 1948 two events occurred that would change the Middle East forever. On the afternoon of Friday the 14th of May, Jewish leaders declared a Jewish State of Israel in what was then called Palestine. Hours later, on the strike of midnight, more than a quarter of a century of British administration of Palestine came to an end.”

Listeners were not told that the end of British administration of the Mandate for Palestine had been included in UN GA resolution 181, passed nearly six months earlier in November 1947.

“The armed forces of the mandatory Power shall he progressively withdrawn from Palestine, the withdrawal to be completed as soon as possible but in any case not later than 1 August 1948.”

On December 11th 1947 the Secretary of State for the Colonies informed parliament that Britain’s administration of the Mandate would terminate on May 15th 1948.

At no point in the programme were listeners informed that the unfulfilled task entrusted to Britain as administrator of the Mandate for Palestine included “placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home”. Hence listeners had no idea that “what was then called Palestine” had been assigned by the League of Nations to the creation of the Jewish national home when they heard Hidalgo’s subsequent statements.

Hidalgo: “As the British left, the war that had been simmering for months between the Jews and the Palestinians filled the vacuum.”

In fact, the conflict that began immediately after resolution 181 was passed in November 1947 did not involve just “the Jews and the Palestinians”: foreign forces in the form of the Arab Liberation Army also took part.

Hidalgo: “On the 15th of May five Arab armies invaded and it fell to the United Nations – then just three years old – to try to negotiate a peace. The United Nations had agreed a plan the previous year to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state and to put Jerusalem under international control. The Jews had agreed the plan, the Palestinians had opposed it. Fighting had intensified even before the British left. Now they’d gone.”

Listeners were not informed that the 1947 Partition Plan (UNGA resolution 181) was non-binding and in fact no more than a recommendation, the implementation of which depended upon the agreement of the parties concerned. The plan was rejected – and thus rendered irrelevant – by the Arab states as well as the Palestinian ‘Higher Arab Committee’ rather than just by “the Palestinians” as claimed by Hidalgo.

With regard to Bernadotte’s two proposals, listeners were told by his son that the first plan was devised by Bernadotte’s aide Ralph Bunche.

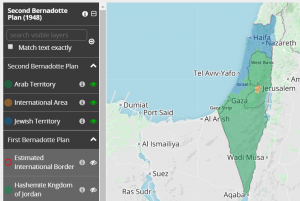

Bernadotte: “It was his plan that my father adopted and was very criticised for. But he then changed to plan number two but it was already a bit too late because the hatred had already started. The point of irritation was that the first plan gave Jerusalem to the Arabs and my father’s second plan – which was really more my father’s plan – was that Jerusalem should be taken out of the fight. It would be a neutral city administered by the United Nations. But even that was unaccepted, from both sides.”

Listeners were not informed that both the first Bernadotte plan and the second Bernadotte plan called for Israel to relinquish the Negev and Jerusalem, leaving it with a fraction of the territory allocated by the League of Nations to the creation of the Jewish national home.

Avoiding the topic of British restrictions on Jewish immigration before, during and after the Second World War, Hidalgo went on to note another aspect of the second Bernadotte plan:

Hidalgo: “Jews had been emigrating to Palestine since the late 19th century and calls for their own homeland had been made more urgent by the Holocaust – the Nazi killing of six million Jews during World War Two. But for Palestinians this meant losing land and villages. They called the creation of Israel al Naqba – the catastrophe. […] The new plan that Folke Bernadotte was working on that summer as well as making Jerusalem a neutral city also sought to deal with the issue of the tens of thousands of Palestinians who’d fled or been expelled from their homes during the fighting. Bertil says the issue of refugees was particularly important to his father.” […]

Listeners heard Bernadotte state that his father’s proposal “insisted…that the Palestinian Arabs should have the right to return to their homes”.

Ignoring the relevant issue of Jews displaced from their homes in places such as the Old City of Jerusalem and Gush Etzion during the same fighting (as well as the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Arab lands), Hidalgo told listeners:

Hidalgo: “That would have had deep implications for the new Jewish state and both Jewish and Arab public opinion were incensed by the proposals for Jerusalem.”

Making no effort to explain those “deep implications”, Hidalgo moved on to the topic of the assassination of Bernadotte in September 1948. Listeners were not informed however that days after the assassination the Israeli authorities enforced the final disbanding of Lehi in Jerusalem.

While the BBC World Service radio’s pick ‘n’ mix approach to Middle East history is by no means novel, it continues to deprive audiences of an accurate and impartial view of events which would enhance their understanding of the background to so many of the contemporary stories it reports.

Related Articles:

REVIEWING BBC PORTRAYAL OF THE 1947 PARTITION PLAN

EXAMINING THE RATIONALE BEHIND BBC POLICY ON ISRAEL’S CAPITAL

WHAT DOES THE BBC TELL AUDIENCES ABOUT THE SAN REMO CONFERENCE?

When the events of the Middle East in the post-WWII 1940s are discussed, the concurrent population transfers in Europe (with approximately 12 million ethnic Germans who had lived throughout Eastern Europe for centuries – in many cases far longer than most Arabs of Palestine- were forcibly repatriated to what was left of Germany with casualties estimated in the low millions) and in the subcontinent (where India and Pakistan had transferred millions with many casualties also) always seem to be passed over.

Only the Arabs of Palestine – who joined with those who sought to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state in defiance of international law as set out through the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine – were subjected to a wholly different standard. If they could show they could live in peace with their Jewish neighbors, they could return to their homes. Of course, this was one of several interrelated conditions set out in the non-binding UN resolution 194 that was rejected in toto by the Arab states lest acquiescence be misconstrued as recognition of the State of Israel.

Imagine the chaos if a “right of return” did exist under international law. Countries would be destabilized by incessant demands from Germans, Hindus, Muslims, Greeks and Turks (and everyone’s descendants) among other affected groups to return to their ancestral homes. And, as this would be painted as some national liberation movement, we are reliably informed that all forms of action, including violence, are not only justified but permitted under international law. There is a good reason, therefore, that no such right actually exists.

For those who claim that those earlier transfers were either voluntary or resolved by subsequent treaty, one need only observe the EU position with respect to Israel: where there is a clear power imbalance between the parties, it is for the stronger to concede to the weaker. Germany, for one, was prostrate in 1945 and had no power to negotiate – which was why their surrender was unconditional. Yet, somehow this rule of negotiations did not seem to apply.

Sad to say, but it nevertheless remains the case that the only difference among all these cases is that when the Jewish people are involved, a separate system of rules is created and applied. Only by ignoring context or outright falsifying history, as among others, the BBC seems wont to do, can this discriminatory regime continue. Is it any wonder that peace remains elusive if the loser is supported in his false confidence that if he holds to his maximal demands that at some future date he will succeed, so don’t give up or give in in the meanwhile?

Let’s compare this BBC view of “intractability” with actual history from around the same period. It is also worth pointing out that the numbers killed in Israel’s ” intractable conflict” are dwarfed by other conflicts before and since:

” Count Bernadotte was killed by Jewish extremists four months after being appointed to try to bring peace to what was already proving to be one of the most intractable conflicts in the world.”

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina on December 19, 1946, and lasted until July 20, 1954. Fighting between French forces and their Việt Minh opponents in the south dated from September 1945.

Followed not long after by the USA in Vietnam:

The Vietnam War (Vietnamese: Chiến tranh Việt Nam), also known as the Second Indochina War,[60] and in Vietnam as the Resistance War Against America (Vietnamese: Kháng chiến chống Mỹ) or simply the American War, was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955[A 1] to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[15] It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. North Vietnam was supported by the Soviet Union, China,[19] and other communist allies; South Vietnam was supported by the United States, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, Thailand and other anti-communist allies.

The French were kept busy in Algeria not long after:

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian War of Independence or the Algerian Revolution (Arabic: الثورة الجزائرية Al-thawra Al-Jazaa’iriyya; Berber languages: Tagrawla Tadzayrit; French: Guerre d’Algérie or Révolution algérienne) was fought between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (French: Front de Libération Nationale – FLN) from 1954 to 1962, which led to Algeria winning its independence from France.

and the USA has had a jolly good war in Afghanistan (and that doesn’t include Iraq):

By the time the U.S. and NATO combat mission formally ended in December 2014, the 13-year Afghanistan War had become the longest war ever fought by the United States.