Judging by the amount of correspondence in our inbox, a great many readers were disturbed by the appearance on June 17th of a long political campaigning article in the magazine section of the BBC News website (which was also promoted on the same website’s Middle East page for four consecutive days) under the misleading title “The Christian family refusing to give up its Bethlehem hill farm“.

Writer Daniel Silas Adamson – described by a “good friend” as a “Middle East writer and campaigner” – uses the former skill to promote the latter aim throughout this deliberately naïve portrait of a story which is in fact considerably less monochrome than either Adamson reveals or the average reader will be aware.

Adamson’s brush-strokes of choice include carefully chosen emotive statements which often fail to stand up to scrutiny, but push the intended campaigning buttons. He opens his article thus:

“A Palestinian Christian family that preaches non-violence from a farm in the West Bank is battling to hold on to land it has owned for 98 years. Now surrounded by Israeli settlements, the family is a living example of the idea of peaceful resistance.”

Clearly, readers are encouraged right from these opening words to sympathise with this ‘non-violent’ family which epitomises ‘peaceful resistance’ (although exactly what that means, they are not informed) and faces the double threat of losing its land and being “surrounded” by “Israeli settlements”.

That latter claim is revisited and expanded by Adamson later on in the article.

“At that time the West Bank had been under Israeli military rule for almost a decade, and Jewish settlers were just beginning to move into the area south of the farm. For the most part, though, the hills around Bishara’s land were still open countryside, farmed by Palestinian families or used as grazing by shepherds. In the 40 years since, Israeli settlements have been built on every one .

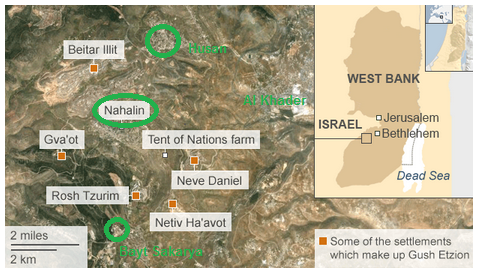

There are five settlements in total, the nearest so close that the settlers’ voices carry across the valley to the farm. The most recent, Netiv Ha’avot, is little more than a strip of houses encircled by coils of razor wire and festooned with Israeli flags. The largest, Beitar Illit, is a town of more than 40,000 people, a blaze of lights on the hillside at night. All of them are considered illegal under international law, though Israel disputes this.”

A map follows those two paragraphs, but as the enhanced version below shows, that map does not clarify to BBC audiences that the Tent of Nations farm is also “surrounded” by various Palestinian villages and towns (marked in green), with the nearest of those being Nahal’in.

And what of the claim that, in 1976, “Jewish settlers were just beginning to move into the area south of the farm”? Well of course the area under discussion here is Gush Etzion and in fact, around the same time as the Nasser family’s Lebanese-born grandfather was registering his land with the British Mandate authorities in the early 1920s, Jews were also buying land in that area: around 70,000 dunams of it, in fact.

Before the Jordanian invasion of 1948, several Jewish communities were established in that area, including Kfar Etzion, Massu’ot Yitzhak, Ein Tzurim and Revadim. The modern-day community of Neve Daniel – whose residents’ voices apparently so inconvenience the peace-loving Nasser family – is built on land purchased by the Cohen family in 1935 from the nearby village of Al Khader.

But Daniel Adamson erases from his long story the fact that these communities were destroyed and any remaining inhabitants not massacred by the advancing British-led Jordanian troops expelled from their lands, and so he is able to present readers with the false idea that, until the mid-1970s, no Jews had lived in that area. Those familiar with Adamson’s previously demonstrated ability to remove Israel’s main tourist attractions from a section of an article about tourism in Israel might not be surprised by this deft sleight of pen.

Adamson’s promotion of the notion that the Nasser family is “battling to hold on to land it has owned for 98 years” is presented in such a manner as to imply to readers that the story of uprooted fruit trees presented at the beginning of the article is part and parcel of that battle. That, however, is not the case.

The Nasser family has had several legal tussles with the Israeli authorities – some still ongoing – including demolition orders for structures they constructed without planning permission and – critically in a place open to the public – without adherence to building safety regulations. That story was publicised at the time in similarly political language to that which this article adopts. Adamson makes no effort to inform readers of the illegal nature of the construction, preferring instead to use the emotive but imprecise language of a propagandist:

“The demolition orders posted on the gate, threatening to destroy the Nassars’ home and water wells.”

In 2006 the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that the Nassers could re-register their land according to Israeli law, but that apparently has yet to be done. However, the section of land upon which the trees which are ostensibly the topic of this article were planted is apparently not included in that Supreme Court decision because it is a separate plot of state land. Our colleague Dexter Van Zile has documented the case and aerial photographs and maps of the land in question are viewable here.

It is important to note that the subject of land ownership in Area C – where the Nasser farm is situated – is far from simple, with old Ottoman, British and Jordanian laws complicating the matter considerably. The photograph of the Nassers’ land deeds from 1924 presented in this BBC article, for example, clearly shows that it is classed as ‘Miri’ land – a specific category under Ottoman land law.

Eventually, of course, this land dispute will likely be resolved by legal process, but what is significant about this story from the point of view of its having being taken up and promoted by the BBC is that, beyond being a land dispute like any other, this particular case – like those of the Nasser family before it – is in the meantime being employed to promote a specific political narrative by campaigners.

Whilst Daniel Adamson’s article is vigorous in its promotion of the Nasser family’s “educational and environmental farm” as a centre of ‘non-violent peaceful resistance’, he does nothing to clarify to readers that it is actually a political project, run at least in part on basis of the contributions – practical and financial – of foreign volunteers and ‘friends of’ groups abroad. Adamson also makes no attempt to inform readers of the political agenda of ‘Tent of Nations’ supporters , its connections to other anti-Israel political campaigns or of Daoud Nasser’s main career as an international campaigner.

The narrative promoted by the Nasser family (an example of which can be seen here) to encourage their ‘peace tourism’ business rests primarily on the painting of a picture very similar to the one depicted in this article: environmentally friendly, peace-loving, ‘authentic’ Palestinians being pressured and crowded out by non-indigenous “settlements” and inexplicably harassed by the Israeli authorities.

In reality, Area C is currently under Israeli administration under the terms of agreements signed by the representatives of the Palestinian people and its eventual fate will of course be decided in negotiations which, under any realistic scenario, will most likely leave the Gush Etzion area under Israeli control. In the meantime, however, political campaigning to influence world opinion continues, with Daniel Silas Adamson having made his contribution in the form of this article and the supposedly ‘impartial’ BBC obviously only too willing to provide generous amplification of his ‘high on emotion, low on facts’ campaigning propaganda.