This is a guest post by Margie in Tel Aviv.

The Economist is currently promoting a seven-part “special report” titled “Six days of war, 50 years of occupation”. The online version of the unattributed sixth instalment of that series of reports goes under the odd title “The half-life on an occupied Palestine“, making one think of a far-flung planet or the moon.

The article carries the misleading strapline “There is no end in sight to the occupation”. Of course an end is in fact a possible: formulas for ending the situation have been offered to the Palestinians time and again by various bodies (with the full agreement of the Israeli government) but the Palestinian leadership refuses in practice to negotiate even though, for outside appearances, parts of it at least foster an impression of enthusiasm.

Three years ago Mahmoud Abbas was offered a plan by the then US president.

“….on March 17, 2014, Obama presented a peace plan to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. It had everything in it, including Jerusalem as a Palestinian capital. It didn’t do any good. Abbas said no.” [emphasis added]

Israelis are frequently told that if Palestinian demands – including Jerusalem as the capital of their future state – are met, there will be peace not only between Israel and the Palestinians but, miraculously, throughout the whole Middle East – if not the world. Israeli leaders are portrayed as intransigent and Palestinians are described as yearning more than anything to be relieved of the ‘occupation’.

Such portrayals, however, do not stand up to the cold light of reality: on his return from Washington in the Spring of 2014, Abbas told his people “I am a hero. I said no to Obama”.

It apparently is not so difficult for Mahmoud Abbas to allow his people to live with the status quo: last November, on the occasion of the 12th anniversary of Arafat’s death, he said “I have no intention of going down in history as a leader who compromised with Israel“. So while the media and the politicians of the world strive mightily to get Israel to do what it is so ready to do, it is actually the Palestinian leader who refuses to end the occupation.

The body of the Economist’s article leads with a description of the Erez Crossing, telling readers that it is “a lucky few” who get to use it.

However, data shows that the “lucky few” are in fact on average 1,000 people a day in one direction alone.

“Every day an average of 1,000 Gazan residents enter Israel through Erez Crossing. The vast majority of these people are those in need of medical treatment, but it also includes businessmen, industry professionals, students, individuals going to pray on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and others. Additionally, Erez is the crossing used by international aid workers, journalists and other internationals to enter Gaza from Israel.”

A glance at any map of the area of course shows that Gaza also has a border with Egypt and there is a crossing for pedestrians there too.

The Economist’s description of Erez crossing includes the following:

“The façade of the Israeli terminal masks a surreal automated facility. No Israeli is in sight as Palestinians emerging from Gaza make their way through remote-controlled gates and scanners. Commands are barked through distorted tannoys, or made with obscure hand signals from behind the blast-proof window of a control room high above.”

Readers are not told that passage through the crossing is automated because those manning it were subject so often to attacks by the Gazans passing through. While the Economist clearly finds that solution unfriendly, Israelis found lethal attacks even more so. The option was to halt the passage of Gazans into Israel or to distance them from contact – and Israel chose the latter.

Later on in the anonymously written ‘Special Report’ readers are told that:

“The Shujaiya neighbourhood, pounded to rubble in 2014, is being rebuilt with scarce materials from charitable donations or, for those who can afford it, the black market. The liveliest bit of Gaza’s economy is the recycling of war rubble.”

The all-important context concerning Shujaiya’s function as a Hamas stronghold and the site of cross-border terror tunnels is absent from the report, as is any mention of Hamas’ misappropriation of materials intended for reconstruction for the purposes of terror.

Following the 2014 conflict between Hamas and Israel a mechanism was established to enable building materials to be trucked into Gaza almost daily. The body that coordinates the entry of those building materials reports that:

“Since October 2014, when the mechanism was established, more than 7 million tons of various types of construction materials entered into Gaza. As of January 2017, 102,331 damaged housing units were renovated out of a total of 130,000, according to the mapping carried out by the UN. More than 11,500 new housing units are in advanced stages of construction, while hundreds are ready for occupancy.

Thus, within 2 years, 224 projects were completed and started operations. Over 500 additional projects are currently being advanced, including the construction of hospitals and clinics, desalination facilities, soccer stadiums, community centers, mosques, schools and more.”

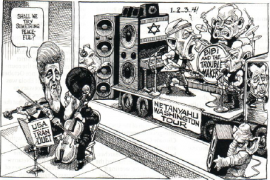

While readers of the Economist’s article hear from Hamas’ Mahmoud al Zahar and Fatah’s Jibril Rajoub, they do not get any first hand insight into the Israeli perspective. Instead, the Economist takes it upon itself to tell its readers what it believes Israelis think.

“There is growing talk in Israel of relieving the economic siege of Gaza, including proposals to build a port on an offshore island (controlled by Israel). One reason is to avoid a return to war. Another is ideological: by treating Gaza as if it were a Palestinian state, Israeli right-wingers think they might more easily fend off pressure for territorial concessions in the West Bank.”

The unidentified writer of the article also knows what Israel should do:

“Those allowed to cross Kalandia by car can take more than an hour. The passage for those on foot looks like a cattle pen. Israel could do much more to make the crossing less awful—more lanes for cars, more staff to process travellers, more effort to clean up the place—without endangering its security.”

Remarkably though, the very relevant topic of Palestinian rejection of years of attempts to bring an end to ‘the occupation’ – from the second Intifada sabotage of the Oslo Accords, through rejection of the Clinton Parameters and the Olmert Plan and up to the 2014 Obama offer – goes completely unaddressed in this article.