A report in The Times by correspondent Josh Glancy missed an opportunity to explore an extremely important, yet rarely covered topic – the injurious impact the Palestinian culture of ‘martyrdom’. What Times readers received instead were cliches about ‘cycles of violence’ putatively caused by Israel’s occupation.

The Feb. 4 piece is titled “Face to face with the West Bank children who dream of martyrdom”, yet Glancy fails to honestly explore the toxic culture of hate and death he’s putatively investigating.

Instead, the message conveyed is that Palestinians have no choice other than to aspire to ‘martyrdom’.

The opening paragraphs are telling:

Mahmoud Tawalbe is 17 and still wears braces. He plays tennis and learns first-aid in his spare time. He is calm and well-mannered, bringing coffee and water to his elders at the Jenin refugee camp’s social club, where he helps out with friends.

And yet, he says, the way that he and most of his peers truly imagine giving back to their community is to die as martyrs. “We talk about the past and our friends who are martyrs,” he says. “There is no hope in the camp, no opportunity. We live day to day.”

Tawalbe sometimes pores enviously over social media shots of teenagers living easier lives elsewhere, the images a constant reminder of life under Israeli occupation in the West Bank. “There’s this feeling the Israelis won’t permit us to have this life,” he says. “A feeling of oppression.”

Boys similar to Tawalbe lie at the heart of this latest round of violence ravaging Israelis and Palestinians. Boys with no hope. Boys frustrated with their narrowed lives, with the unending Israeli military presence, with the corrupt and useless Palestinian National Authority. Boys being raised to believe that to die fighting the Jews is an act of eternal glory.

Tawalbe is named after his uncle, also Mahmoud Tawalbe, a revered Islamic Jihad terrorist killed in 2002 during the second intifada. The generational burden upon his nephew is obvious.

In fairness, Glancy does acknowledge that teens like Tawalbe are raised to believe that murdering Jews represents their highest aspiration.

However, he fails to follow through by exploring the impact of a societal pathology in which youth are indoctrinated with such lethal antisemitism – groomed from birth to see their own death in the service of that hatred as an act of community service.

Nor does the Times reporter seem to consider that the terror resulting from the inculcation of teens like Tawalbe with an ideology glorifying violence is an enormous impediment to ending the occupation.

Note also that the uncle who he was named after was not merely a PIJ terrorist, but one who was responsible for numerous deadly attacks against Israeli civilians during the 2nd Intifada, a five-year campaign of violence (which erupted three months after PA leaders rejected an Israeli peace offer) that arguably did more than anything else since Oslo to erode the ‘peace process’.

Glancy, evidently attempting to tie in the narrative of hopeless Palestinian children to recent terror attacks, then describes the terrorist who murdered seven Israeli civilians in Jerusalem on Shabbat as a “boy”, despite the fact that he was a twenty-one year old man.

These are boys like Khairi Alqam, 21, who killed seven Jewish civilians outside the Ateret Avraham synagogue in east Jerusalem on January 27.

Pivoting to prospects of a 3rd Intifada breaking out, a topic raised frequently in mainstream media outlets in recent weeks, Glancy writes:

Something dangerous is rising in the Holy Land. Some are predicting a third intifada — a full-scale Palestinian revolt similar to the devastating uprisings of 1987-93 and 2000-05. Others merely expect this current round of violence to deteriorate further, becoming a “new normal”. As many as 180 Palestinians and more than 30 Israelis have died since the beginning of last year.

As we’ve noted previously, a large majority of the Palestinians killed since last year were terrorists or otherwise involved with violent clashes with Israeli soldiers, while the overwhelming majority of Israelis killed were civilians.

Glancy continues:

The second intifada was centred on Jenin, in the northern West Bank. Its refugee camp is both a symbol and source of violent resistance to Israel. It was here that the Battle of Jenin was fought in April 2002, as Israeli tanks rolled in to crush terror cells, claiming more than 50 lives.

In fact, the death toll was 75 – 52 Palestinians killed, mostly terrorists, and 23 Israeli soldiers killed.

The article continues:

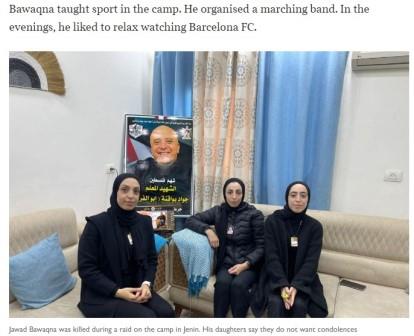

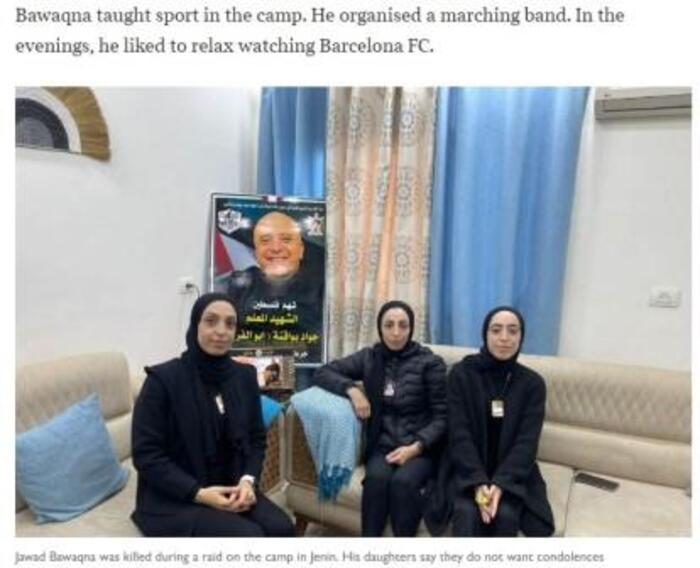

Last month, there were echoes of 2002. On the night of January 26, Israeli troops stormed the camp and killed nine people, seven of them gunmen, two of them civilians. On January 19, troops killed Jawad Bawaqna, 57, a sports teacher, during a raid on the camp.

When I visited a week later, the camp was gripped by a sense of numb fury. Outside Bawaqna’s house, the walls were covered with pictures of the smiling father of six.

Bawaqna, his daughters say, was shot by an Israeli soldier as he sought to help a militant who had been shot on his doorstep. They witnessed his death. “He was full of life, fun to be around, young in spirit,” said his daughter Alaa, 34. “He was a feminist.”

Bawaqna taught sport in the camp. He organised a marching band. In the evenings, he liked to relax watching Barcelona FC.

In fact, Bawaqna was not just a “sports teacher”, but a Fatah operative, a fact made clear in the very photo (per CAMERA Arabic researchers) used in The Times article:

Later, Glancy writes:

Death rules over life in the Jenin camp. At the local toy shop, alongside the Barbies and teddy bears, is a rack of neck pendants with pictures of fallen fighters on them. The walls outside the shop are plastered with pictures of the fallen. Fresh posters are pasted over tattered older ones, creating a palimpsest of martyrdom. It is an abyss.

The camp — home to about 11,000 — is governed under a different jurisdiction from the neighbouring town of Jenin and is far more dilapidated. Many of its residents are the descended from refugees of the original 1948 war with Israel, which they call the Nakba — catastrophe. They still hope one day to return to Haifa and Jaffa.

As long as this place exists, so will conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

Again, the Times journalist misses an opportunity to shed light on some of the key drivers of the conflict: the fallacious Palestinian belief that millions of them will one day “return” to places in Israel where their ancestors may have once lived; and the fact that Palestinians leaders, their Western supporters and (especially) UNRWA perpetuates their misery by continuing to house them in such ‘camps’, rather than assimilate them into proper Palestinian cities, while nurturing the fantasy of their eventual ‘return’.

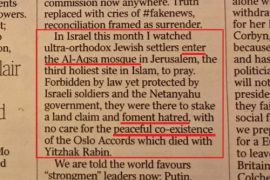

But, it’s a paragraph near the end of the article where we see most glaringly not only the journalist’s penchant for denying Palestinian agency, but an illustration of the media’s tendency to employ abstractions which blur cause and effect:

But there is no peace process. There is only the endless“situation” drawing another generation into its morbid grip. Robbing Asher Morali of his young life. Pushing Mahmoud Tawalbe and his friends into a cycle of martyrdom.

The 14 year old boy, Asher Morali, killed in Jerusalem’s Neve Ya’akov neighborhood, along with six others, on Holocaust Rememberance Day, didn’t lose his life as the result of being the “grip” of a “situation”.

He was murdered because a particular Palestinian man, Khairi Alqam, made the conscious decision to open fire on a group of Jewish civilians near a synagogue. And, if the 17 year old Mahmoud Tawalbe follows in his uncle’s footsteps and, one day, also murders innocent Israelis, it will be because of a choice that he made of his own volition.

The ultimate irony is that pro-Palestinian activists and their supporters sometimes claim that all they desire is for Palestinians to be “humanised”, while simultaneously infantilising them, and imagining that the normal laws of causation – what commentator Rob Henderson describes as the “reliable connections between good choices and good outcomes and bad choices and bad outcomes” – don’t apply in their situation.

A more dehumanising portrayal would be hard to imagine.

It appeared side by side with a report on the Peshawar mosque bombing. But, strangely, that wasn’t entitled “Face to face with the Taliban children who dream of martyrdom”, yet it’s exactly the same culture of Islamist victimhood and ultra-violence.

The confusion of cause and effect is crucial to maintaining the false equivalence between terrorists and their victims, including lazily refusing to take account of victims organizing a proactive self-defense action, as in Israeli raids seeking out terrorist cells before they can strike.