An obituary about a gentleman named John Watson –written by one of his former commanders and appearing in the Guardian on March 29th – contains an interesting paragraph.

“His battalion was posted to Palestine in 1948, as the British Mandate came to an end. Watson was appalled by the imminent destruction of the new state of Israel – attacked as it was on four fronts and wholly undefended by the British army. He thought it morally wrong that Jews, who had experienced so much already, should be slaughtered, again. Rifle in hand, he went over the wall to volunteer with Haganah and take part in front-line combat. In the siege of Jerusalem he was wounded. After the conflict he worked on a collective farm, where he met Ora, the woman he married. They went on to farm for four years.”

This account reminded me of the experiences recounted by a now deceased great-uncle of mine who also served with the British army in what was then Palestine during the British Mandate and which has been on my mind quite a bit recently since the screening of Peter Kominsky’s ‘The Promise’ on British television.

Kominsky’s selective view of events during the Mandate years, supposedly based on interviews with former British servicemen, did not reflect my uncle’s accounts of pretending not to notice Jewish refugees trudging up the beaches along Israel’s coast or the effort he and other low-rank soldiers apparently put into not discovering weapons caches on the kibbutzim he was sent to search. He also told me of friends who, unlike himself, did not return with their battalion to the UK, but deserted and stayed in the emerging Jewish state, some to fight with the Israeli forces and some because of love for a local girl. Although they did not serve in the same battalion, I now wonder whether my uncle and Mr. Watson ever met.

As anyone familiar with Israel knows, six degrees of separation are usually a few more than necessary here, and seeing that it is possible that Mr. Watson served with ‘Machal’ – the unit of foreign volunteers which still exists today but is best known for the vital part it played in Israel’s War of Independence, I also wonder if he ever met a young Jewish American volunteer who arrived here to fight in that war and later married my father-in-law’s sister.

He could even have met my father-in-law himself, as he too served in Jerusalem during the siege in 1948. Or perhaps Mr Watson was one of those who used to enjoy a hearty meal provided by my father-in-law’s mother from one of her famous ‘bottomless cooking pots’ (there was always enough for everyone) to the people about to set off from their street corner on the convoys taking supplies to besieged Jerusalem.

The Guardian allotted quite a bit of column space to ‘The Promise’ which, despite being no more than a drama, seems to be regarded by some (including its creator) as an accurate account of history because it taps into their own prejudices and political bias.

But as Mr. Watson’s life story shows, there is another side to Kominsky’s subject matter which is too often brushed aside or contorted because it does not fit in with the accepted narratives of the type promoted by Kominsky, the Guardian and many others.

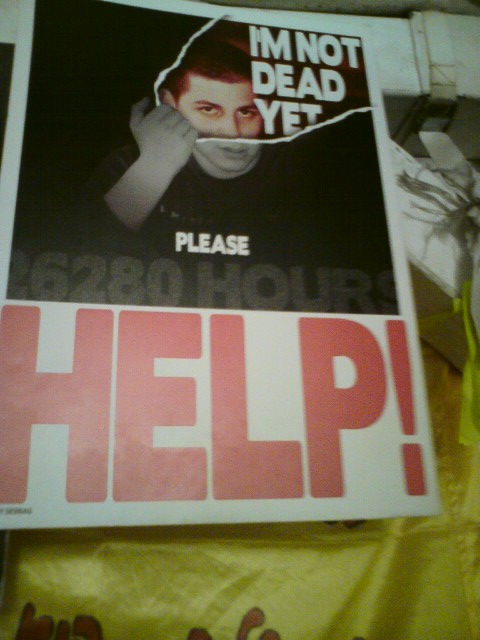

John Watson – may he rest in peace – is no longer with us to give a first-hand account of the turbulent birth of Israel. Neither is my great-uncle, my father-in-law’s sister’s husband nor his mother. My father-in-law himself, however, is now 83 and I have been thinking for some time that I must take him and a video camera to Jerusalem whilst he is still amazingly lucid and fit in order to record his memories of those years.

Such documentation may well be all we have in future years with which to refute the kind of politically motivated ‘historical’ fictions proffered by those intent upon rewriting Israeli history in order to try to dictate the future.