Before we properly examine a Guardian article (The two-state solution in the Middle East: Everything you need to know, Dec. 28th) by the paper’s former Jerusalem correspondent Harriet Sherwood, let’s first provide a short textual analysis:

In an article putatively providing readers with ‘everything you need to know about the two state solution but were afraid to ask’, here’s a count of the number of times the following words were used in the text, headline and strap line:

Settlements (4); Hamas (1); Terrorism (0); Rockets (0); Incitement (0); Extremism (0); Antisemitism (0)

As you’ll see, the appearance or absence of these words are crucial to understanding how Harriet Sherwood misleads readers over the failure of the two parties to achieve an agreement.

After an introductory paragraph explaining the basic idea of a two-state solution, Sherwood devotes several paragraphs to the obstacles. Here’s the first one:

Past negotiations have failed to make progress and there are currently no fresh talks in prospect. The main barriers are borders, Jerusalem, refugees, Israel’s insistence on being recognised as a “Jewish state” and the Palestinians’ political and geographical split between the West Bank and Gaza.

First, Sherwood fails to mention that the Palestinians rejected at least three recent serious Israeli peace offers, which included a contiguous Palestinian state, since 2000.

As far as the main barriers, she correctly notes some of the serious issues, but omits others – such as continued Palestinian terror, incitement and extremism, and the fact that part of the territory in question – Gaza – is ruled by a terror group which rejects the continued existence of a Jewish state within any borders.

Note also how Sherwood frames the issue of recognizing Israel as a “Jewish state” as a problem only insofar as Israel “insists” upon it, rather than the Palestinian rejection of such recognition.

Sherwood’s section on obstacles to peace continues:

The Palestinians demand that the border of their new state should follow the green line, giving them 22% of their historic land. But Israel, which has built hundreds of settlements on the Palestinian side of the green line over the past 50 years, insists that most of these should become part of Israel – requiring a new border which would mean, according to critics, the annexation of big chunks of the West Bank. Land swaps could go some way to compensate but negotiations have stalled on this fundamental issue.

First, the word “border” is not accurate when referring to the 1949 armistice lines. They are boundaries which are to replaced in the future by a negotiated, internationally recognized permanent border.

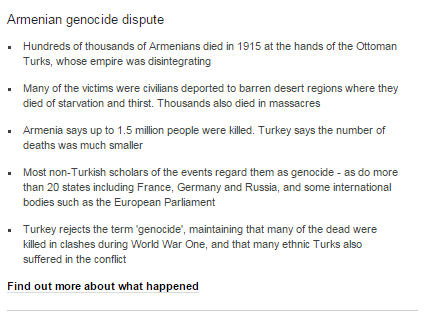

More importantly, the claim that Palestinians are (magnanimously) only asking for “22%” of their “historic land” is erroneous. First, what “historic” Palestinian land is she referring to? There has never been, at any point in history, a sovereign Palestinian state, and a unique Palestinian-Arab national identity – distinct from Arab and tribal identities – itself is a recent development, going back no further than the 1920s.

Of course, prior to Israeli control of Gaza (until 2005), the West Bank and east Jerusalem, the territory was controlled by Jordan, the British and the Ottomans (and, in the case of Gaza between 1949-67, Egypt).

Further, the 22% figure (which presumably represents the land they’re demanding now in relation to the total land mass of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza) implies, as Shani Mor argued at The Tower, that Palestinians have conceded 77 percent of their historic claims, “implicitly saying that all of Israel proper somehow belongs to them.” Plus, if you want to argue from a territorial maximalist position, Israel (even in its current form) has conceded most of their land as promised to them under the 1922 Mandate for Palestine – arguably the earliest modern legal codification of an area known as “Palestine”.

Sherwood’s list of obstacles continues:

Jerusalem is another obstacle. Israel has said it cannot agree any deal which sees the city shared or divided between the two sides. The Palestinians say they will not cede their claim and access to their holy sites, all of which are located in East Jerusalem, on the Palestinian side of the green line.

First, irrespective of what the current Israeli negotiating position is today, previous Israeli offers of statehood did include Israeli withdrawal from Arab neighborhoods of east Jerusalem and would have placed the Old City, including the Temple Mount, under international control.

Moreover, Sherwood’s assertion that “Palestinians say they will not cede their claim and access to their holy sites” is a non-sequitur, as, even under current Israeli control of the Old City, Palestinians have access to their holy sites. Nobody on the Israeli side is even suggesting that a two-state agreement would demand that the Palestinians cede access to their holy sites. The question narrowly pertains to who would ultimately have security and administrative control of the contested area, not to access.

Sherwood lists another obstacle to two states:

The Palestinians have long insisted that refugees from the 1948 war and their descendants should have the right to return to their former homes, although many diplomats believe they would settle for a symbolic “right of return”. Israel rejects any movement on this issue.

First, Palestinian demands that millions of Palestinians who have never been refugees should have the “right” to “return” to places in Israel they never once lived are absurd. It’s also simply not true that “Israel rejects any movement on this issue”.

As the Palestine Papers revealed, Ehud Olmert agreed, during 2008 talks, to take in 1,000 Palestinian “refugees” per year for five years, and agreed to monetary compensation to “refugees” as well. Further, in the most recent round of negotiations between Netanyahu and Abbas, Netanyahu (according to a detailed analysis of the talks published in July, 2014 by Ben Birnbaum and Amir Tibon in The New Republic ) agreed to “monetary compensation to Palestinians displaced in Israel’s War of Independence” and the “return” of an unspecified number of Palestinian “refugees”.

Sherwood continues:

Israel insists that the Palestinians must recognise Israel as a “Jewish state”. The Palestinians say this would deny the existence of the one in five Israeli citizens who are Palestinian.

Though it’s unclear what “denying the existence” of Arab citizens of Israel even means, if the concern is over the civil and legal rights of Arab Israelis, it’s difficult to understand how the mere acknowledgment by Palestinian leaders of Israel as a Jewish state would in any way impact their status of full citizens with equal rights under the law.

Sherwood continues:

Any potential deal is complicated by the political breach between Fatah and Hamas, the two main Palestinian factions, and the geographical split between the West Bank and Gaza.

As we noted above, any deal isn’t merely complicated by the “political” and geographical “breach” between Fatah and Hamas. It’s “complicated” by an unbridgeable ideological division. Whilst the PA at least officially accepts the two-state solution, Hamas is an Islamist extremist movement which rejects the continued existence of Israel, and whose leaders have openly called for genocide against Jews.

Indeed, Sherwood’s specific failure to focus on Hamas in her “briefing” on obstacles to two states is indicative of a broader omission of extremely important context. Though most Israelis still favor two states in principle, you can not seriously discuss plans to restart negotiations for a final agreement without addressing Hamas’s role in the disastrous results of the last attempt to trade ‘land for peace’.

The question for most Israelis who are serious about peace but wary of Palestinian intentions is not necessarily the particulars of the final agreement, but the question of what will happen in the days, weeks, months and years after such a deal is implemented.

Will Palestinians use their new freedom to become responsible political actors, adopt democratic institutions, nurture a culture of peace and take serious steps to fight terror, incitement and extremism with the same fervor as they fought the occupation?

Or, will Israel face another Gaza?

Will painful territorial concessions not only fail to end the conflict, but in fact give rise to an extremist group on another border, rendering nearly the entire country within range of rocket fire?

Will Israelis have to watch as another generation of their children are caught within the insidious cacophony of sirens, screams and shrapnel – the unforgiving reality of endless war and trauma brought upon by the chimera of an “inevitable” peace?

Beyond the bias within this specific Guardian analysis, the truth is that UK media coverage of negotiations similarly suffers from the failure to take Israeli concerns seriously – rational fears born of the failure of past territorial withdrawals to bring peace, and a refusal to ignore the reactionary Palestinian political culture which – most Israeli believe – lays at the root of the conflict.