The objective of Raja Shehadeh’s Guardian op-ed – as illustrated by the headline, “Issa Amro’s plight highlights Israel’s intolerance of even nonviolent protest” – is to obfuscate Palestinian violence whilst alleging that Jerusalem harshly cracks down on even non-violent protesters.

The first attempt by the Palestinian writer to sell credulous Guardian readers on this premise is found in this early paragraph:

On 6 January, Issa Amro, a UN-recognised human rights defender, and the founder and coordinator of Youth Against Settlements, a Hebron-based group, was convicted in an Israeli military court near Ramallah on six counts. He was first put on trial in 2016 on 18 charges dating back to 2010, including incitement, insulting a soldier and participating in a march without a permit.

However, as the Reuters article he uses as his source makes clear, Amro, an ‘activist’ from Hebron, wasn’t found guilty of merely “insulting a soldier”. Rather, the charge was for “assaulting” an Israeli.

Here’s the relevant sentence from the Reuters article:

Amro denied the charges, which included protesting without a permit, obstructing Israeli soldiers’ activities in the flashpoint city of Hebron and assaulting a Jewish settler.

Whether Shehadeh’s error was intentional or not is impossible for us to know. However, it’s telling that the same Reuters article also adds the following, on additional charges by the Palestinian Authority against Amro:

Amnesty said the PA has accused [Amro] of “disturbing public order” and “insulting higher authorities” over Facebook posts in 2017 critical of Palestinian leaders.

So, the Guardian contributor somehow managed to conflate the charges, obfuscating from readers that it was the Palestinian Authority that charged Amro with “insulting” authorities, not the Israelis.

The op-ed’s framing continues:

Following the violent period of the second intifada (2000-2004), Israel restricted Palestinian movement by placing more than 500 roadblocks throughout the West Bank. Now that the country is living through one of the least violent periods in its history, what justification remains for keeping most of these restrictions in place?

This is misleading in two respects.

First, CAMERA UK has continually documented that, whilst the number of casualties resulting from terror attacks has been relatively low, the number of actual terror attacks (the goal of which of course is to kill Israelis) remain high. In 2020, there were over 1500 terror attacks – based on reports from Israel’s Security Agency.

Also, it’s likely that the reason why the number of Israeli fatalities is so low – despite the high number of attacks – is directly related to the security measures (including roadblocks) Shehadeh complains about.

The op-ed continues:

The most extreme example of these obstacles to movement is in the Old City of Hebron, a once vibrant centre for trade and commerce serving a population of 220,000 Palestinians from the city and its surrounding villages. This historic area is now termed H2, home to several hundred Jewish settlers – in violation of international law – where in one square kilometre there are 21 permanently staffed checkpoints.

However, the Israeli presence in the historic Jewish city was agreed to by the Palestinian Authority under the terms of Oslo II, which involved an IDF withdrawal, in the late 90s, from 80% of the city. The agreement divided Hebron into two sectors, H1 (Palestinian control) and H2 (Israeli control). As H2 only represents 20% of the total territory of the Hebron, it means that Jews are barred from 80% of the city.

Shehadeh then argues that there is no legitimate “security rationale” for “extreme restrictions in the Old City of Hebron, which ignores that the city has long been a hub of terror. During what’s known as the Stabbing Intifada, in 2015-16, dozens of attacks occurred in Hebron. And, as recently as 2018, Israel’s Shin Bet uncovered an extensive Hamas network in the city, which was planning attacks, raising funds and facilitating the group’s infiltration into the city’s charitable and municipal institutions.

The op-ed continues:

It takes strong conviction to face such injustice and respond to it with nonviolence. This kind of resistance marked the first Palestinian intifada (1987-1993).

The claim that the First Intifada was “non-violent” has been refuted on these pages previously. In fact, roughly 160 Israelis were killed and thousands more wounded during that period of “non-violent resistance”, in addition to the thousands of Palestinians murdered by Palestinian vigilantes accusing them of being ‘collaborators’.

Shehadeh then adds:

After 2000, many have tried shooting and stabbing soldiers and settlers.

The suggestion that ‘only’ soldiers and settlers were targeted by Palestinian terrorists during the Second Intifada is of course a lie, as most attacks targeted civilians (roughly 70% of the total fatalities), and most were within the Green Line.

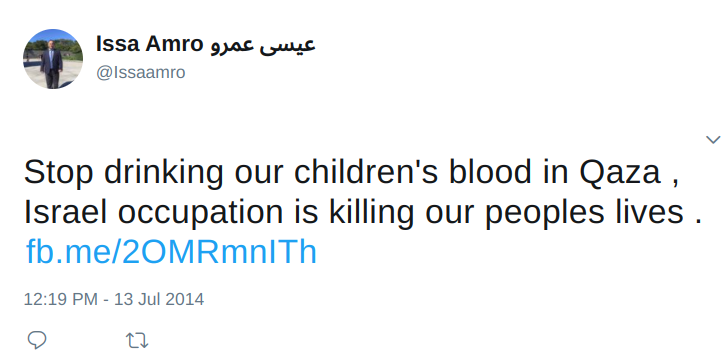

Finally, let’s address Shehadeh characterisation of Amro, the protagonist in his tale, as some sort of progressive ‘human rights activist’. First, as the late Petra Marquardt-Bigman documented, Amro tweeted explicitly antisemitic content.

Amro, who’s been framed as the “Palestinian Ghandi” by other media outlets has also rooted for a Third Intifada on social media repeatedly. His group ‘Youth Against the Settlements’ referred to Palestinian terrorists killed by Israeli forces while they were in the act of carrying out an attack as “martyrs“, and has engaged in incitement with the libel that thousands of settlers were “storming the Ibrahimi Mosque” in Hebron.

Of course, the mosque is known by Jews as the Cave of Machpelah (Tomb of the Patriarchs), and it is considered Judaism’s second holiest site. So, even if those Jews shown in the photo entered the building, they were simply visiting a site that’s extremely holy to Jews. The “storming the mosque” libel has been used for generations – usually in connection to Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem – to incite violence against Jews.

As such, it’s not difficult to understand why Amro would be charged with incitement, and why the Guardian op-ed’s claim that he’s a “peace activist” is absurd.